The Clarion Herald reports on the AEC

You can read the article below, or on the Clarion Herald.

Falling Asleep To The Clickety-Clack Of Success

By Peter Finney Jr., Clarion Herald Commentary

Linda Phoenix Teamer was 19 years old in 1970, the year after Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon.

Peter Finney Jr., Clarion Herald Commentary

One of Teamer’s wistful teenage dreams as a student at Joseph S. Clark High School in New Orleans was to become NASA’s first African-American female astronaut, but first she had to come to grips with the mysterious forces of social gravity, something incapable of being plotted by Sir Isaac Newton.

In New Orleans, the business world into which Teamer wanted to plant her flag was about as white as Armstrong’s flight suit.

Teamer, now 66, had just graduated from Clark and was studying business administration as a freshman at LSUNO when a friend told her about an unusual, tiny school on Exchange Place in the Central Business District, mostly for African-American women, that not only offered to pay students a small weekly stipend but also virtually guaranteed them ready-made secretarial jobs upon graduation with major oil companies in the city such as Shell and Exxon.

It was called the Adult Education Center, which for seven years (1965 to 1972) streaked across the sky with a small staff emboldened by the vision of one woman, preparing 431 students with typing, shorthand, speech and etiquette skills that forever would change the trajectory of their lives.

Teamer never became an astronaut, but after serving for six years in the accounting department at Shell in the old International Trade Mart on the Mississippi River, she worked for 30 years as a flight attendant for Delta Airlines, visiting places across the globe, places on a map she never could have imagined when, as a 14-year-old living in the Lower 9th Ward in 1965, Hurricane Betsy swallowed up her family’s home in the 1800 block of Flood Street.

One day, sitting on a bench outside St. Peter’s Square and gazing at the Roman basilica that she knew as the heart of her Catholic faith, Teamer reflected on the teacher who had made such a moment possible – Alice Geoffray, the cofounder of the Adult Education Center.

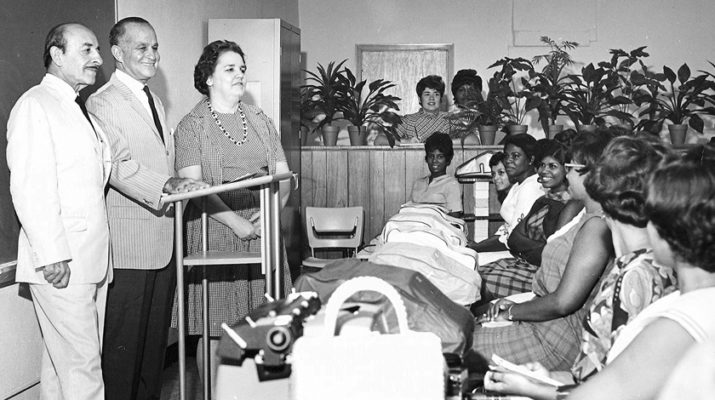

New Orleans Mayor Vic Schiro, left, businessman James Coleman Sr. and Alice Geoffray address students at theAdult Education Center in 1965. The school lasted just seven years but changed lives forever.

Photo | COURTESY JEANNE GEOFFRAY

“We called her our guardian angel,” Teamer said. “She was so remarkable and amazing to us. We all realized that here was this Caucasian lady who somehow wanted to help us out. We couldn’t see any benefit for her. She had seven children of her own. She was our warrior.”

Geoffray, who died in 2009 at age 84, is one of those characters cut from the cloth of Dorothy Day. She graduated from St. Mary’s Dominican High School and St. Mary’s Dominican College, and after rearing seven children, she began teaching, like her husband, in public school to help keep the red beans and rice on the table. She taught vocational education at Rabouin High School in the CBD.

When a former Dominican priest, Timothy Gibbons, saw a chance in 1965 to start the Adult Education Center, he tabbed Geoffray as exactly the women he needed.

“He hired her as his secretary because he heard she had a very good reputation, as much with the students as with the employers around New Orleans,” said Jeanne Geoffray, Alice’s daughter. “But he was on his way out of New Orleans, and he dumped the whole program on her.”

In those days, even finding a home for the school was an exercise in defying the forces of social gravity. Gibbons and Geoffray approached 59 landlords to lease space, but when the building owners found out the purpose of the new venture, the buildings suddenly became unavailable.

Finally, businessman James Coleman Sr. stepped up and offered the Exchange Place location. Federally funded at its start, the school was equipped with IBM Selectric typewriters, a state-of-the-art speech lab and a time clock that students, dressed for an office job after lessons in “personal dynamics,” dutifully punched in every morning.

Dominican Sister of Peace Rose Bowen, 91, attended the school’s first graduation ceremony and came away so impressed with Geoffray that she asked her principal at Dominican High School to allow her to teach all of her classes in the morning so that she could go to the CBD and be one of Geoffray’s teachers in the afternoon.

“I just said to myself, ‘I would like to teach with that woman,’” Sister Rose said from Columbus, Ohio. “The amazing thing was the way she addressed the whole person. She had a course on novels so that when the women got into an office setting, they would have a sense of familiarity with those books. She was trying to get them to be at ease as conversationalists.”

Sister Rose said students were so inspired because they had seen what previous graduates had gone on to achieve, and they wanted to row in the same direction.

Stepped in to help

When one of the prospective graduates couldn’t afford a nice dress for graduation, Sister Rose said “Alice told her to get a dress and put it on her account. She told me, ‘You know, I have to dress professionally and nicely, but I don’t have to have really exceptionally good-looking clothes. I would rather give it to a girl who needs it.’”

Geoffray’s own children were partners in the school’s success, often taking the bus after school to do their homework in the CBD. Jeanne Geoffray, the sixth of seven children, attended Fortier High School.

“The reason I didn’t go to Dominican was we didn’t have the money,” Jeanne said.

Jeanne said her mother made room in the family home for an unwed, pregnant student. After the student delivered her baby, she placed the baby for adoption with Catholic Charities.

Other students felt Geoffray’s protection.

“There was one young woman whose husband had abused her, and she came to school with black-and-blue marks,” Sister Rose recalled. “One of the other students told me she was going to do whatever she could to hang on and get through school because she could see what it would mean to her.”

The school had an incredible success rate. About 94 percent of the students graduated and went on to quality, good-paying jobs, Jeanne Geoffray said.

“There were tutors who would sit you down because they didn’t want to lose anyone,” Teamer said. “They wanted to make this program work by any means necessary.”

Jeff Geoffray, the youngest of Alice’s children, and Jeanne are collaborating on a book about the Adult Education Center. Jeff is a movie producer in California, and he knows his mother’s life is a story waiting to explode onto the screen. It is so rich that it might take the form of a long-form series rather than merely a two-hour film.

It’s that big. She was that big.

“My mom was a Catholic, and she knew the Golden Rule,” Jeff said. “That’s what she lived by. She wasn’t about changing the world, but she knew that there was a need with these women. She thought, ‘We can teach them skills and get them jobs.’ She told us she had never been in an environment where the students wanted to learn so much.”

Sweet sounds of success

Pamela Wimbley was the youngest of four sisters who attended Geoffray’s school. Even before she set foot inside, she had heard all about it from her eldest sister Carol, who didn’t have to say a word.

Every night, as Carol practiced her speed typing on the manual typewriter she had rented to help her improve, Pamela would be in her bedroom, trying her best to fall asleep. Carol was pushing herself to reach the 32 words-per-minute required of a Shell Oil secretary.

“Whether it was the constant clickety-clack of the keys hitting against the paper as she spelled each word aloud, the ping of the bell signifying she had come to the end of the margin or the sound of the carriage return to start anew, it was good to my ears,” Pamela recalled. “It was a sweet lullaby that would sing in my ears, until I fell off to sleep.”

Peter Finney Jr. can be reached at pfinney@clarionherald.org.